Anders Danielsen’s lie is not your average hyphen

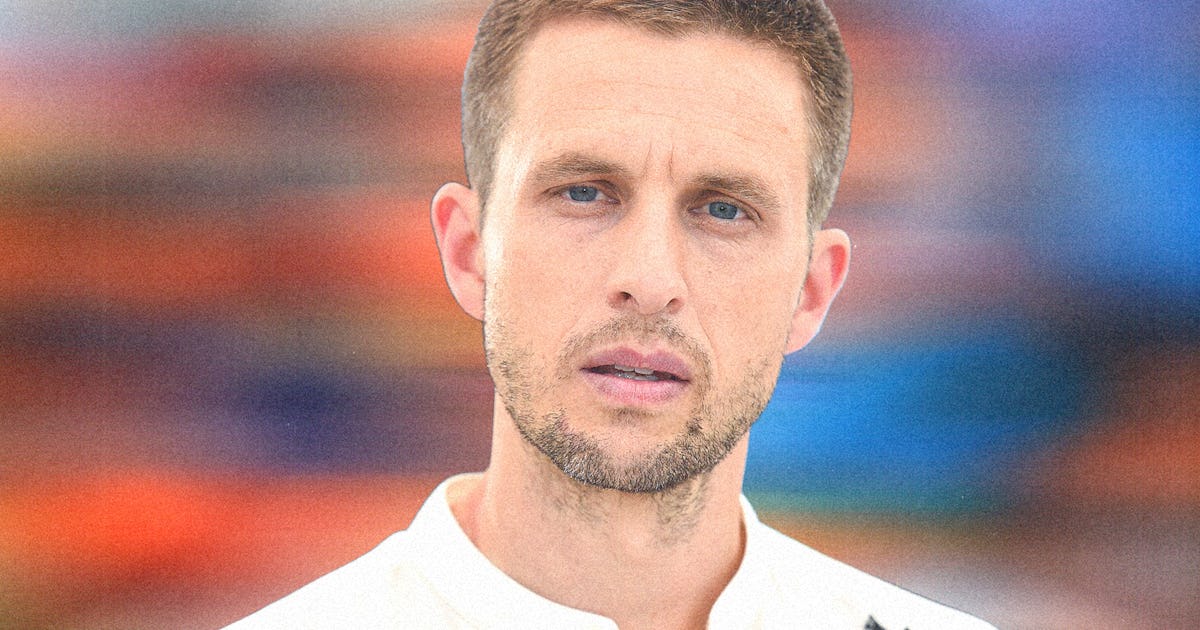

The movie industry is full of talent with many hyphens, but one label you don’t see every day is “actor-slash-doctor.” Over the past two decades, Oslo-born Anders Danielsen Lie has pulled off a rare double feat: starring in a string of acclaimed European art films while pursuing a career in medicine. This isn’t a novelty act – his best-known roles are in three acclaimed plays by auteur Joachim Trier that have performed at festivals from Cannes to New York. Together they form a disarming triptych of modern melancholy and missed connections, ranging from the vague feeling that life is beginning to slip away from you to the daunting ends of depression.

Lie’s characters have a way of creeping up on you with the depth of their intensity – the actor outwardly suggests an unassuming guest at a friend’s dinner party, who actually proceeds to unfold a heartbreaking story with a pale smile. Trier’s “Oslo trilogy” with Lie began 15 years ago with Repriseportraying him as a struggling young writer, and continued dark character study Oslo, August 31in 2011. It now ends with The worst person in the world, a warm and comically sad portrait of a woman in her twenties, Julie (Reinate Reinsve), who is testing her next steps. Lie, 43, plays Julie’s boyfriend Aksel, a quietly neurotic comic book artist from an older generation who is beginning to feel his age.

The worst person in the world opens February 4 and is Norway’s entry for the Best International Feature Film Oscar. It’s not even Lie’s only film of the past year: he also starred in Mia Hansen-Løve Bergman Island, which opened last October and, along with the film Trier, screened at the New York Film Festival. That’s when I spoke with Danielsen Lie on a blustery fall day at a noisy French restaurant in Midtown. Always polite and personable, the actor also poignantly mentioned that he had read fellow countryman Karl Ove Knausgård’s latest novel. Below, he talks about his non-traditional career path and the therapeutic nature of films from Trier.

How did you approach Aksel’s role in The worst person in the world?

I tried to focus more on the relationship and build chemistry with Reinate, so the audience would see it from her perspective. And I wanted it to represent a theme more than a character. It represents the melancholy of passing time. She’s right in the middle of the chaos he may have been through a few years ago, so they’re out of sync. It’s the “bad timing” side of the romantic comedy, which is also quite melancholy, because that’s how life is. We’ve all met people where we dream of what it might have been like to meet that person at another time.

Aksel is also at a point of transition, but he doesn’t fully realize it.

Yes. Throughout most of the movie, there’s this contrast between him being the wise, mature character and her being in the middle of life’s decisions and general existential confusion. But he’s more lost than you think. Identity is a work in progress for almost everyone. At least it is for me. I feel more confident now, and there are things in my life that I’ve acknowledged and accepted, but I can still have days where I wonder, “Who the hell am I?” [Laughs.]

Speaking of which, you’re both an actor and a doctor. What is your medical specialty?

I am still in the process of specializing in “general medicine”, which is a specialty in Norway. It’s not really family medicine, but…

Like a general practitioner?

Yes, it’s a long course where working as a general practitioner is an important part of the specialty. [Acting and being a doctor] is not a combination I would recommend to others. [Laughs.]

And now you’re stuck.

Yeah, I’m stuck. You know, I’ve always been somewhat ambivalent about acting.

Why?

I do not know. I think part of that is because I don’t have any formal training. So I spent a lot of time finding a way to not always “use” myself in a certain way. Especially in a film like this, the acting style is so close to real life, and it demands naturalism, emotionally and in every other way. If you’re going to do this in a lot of movies, you need to have some sort of method so you don’t end up totally confused as to who you are. [Laughs.] Sometimes I’ve been concerned about being too pigeonholed.

How are you typed?

Sometimes I feel like I end up being, well, “the depressed, melancholy person.” I would like to do different things and develop a little [of] What can I do. But you never really walk away from yourself.

In Bergman Islandyou give your character, Joseph, a kind of mystique.

Yeah it’s true. My experience was – if it was a post-it on my wall – “no character”. I wanted him to be like a Bressonian model and for the public to project their expectations towards this character. Because he’s a character in his storyline, and there’s almost a mythological, fabled quality to the love story. And he’s also a lover, isn’t he? So I wanted there to be a mystical veil and I wanted it to be dark.

You also play a doubly fictional character, as Joseph is a character in a story told by another character.

Yeah! And I was just talking with someone about how Joachim’s films are almost like a documentary. Reprise felt like a documentary from the fall of 2005. This film had an impact on my own life – from meeting my wife to acting. I had no intention of acting.

Reprise wasn’t your first screen role?

I made a movie when I was a kid. It was about a 10 year old child who is losing his hair. But when Reprise arrived, I still had a year left in medical school. I remember I was reading for a forensics exam. I received a phone call from a production company asking if I wanted to audition for Joachim’s first film. I did not know Joachim. At first I said, “Thanks, but no thanks.”

But you ended up doing it.

I read the script, and I was like, okay, this is all I am worried about. And I was working with young adults with mental illnesses at the time, and I was supposed to play someone with mental illness, so it made sense to give it a shot. Joachim’s films are fiction, of course, but there are elements of our own life, people we have seen, people we know. So there’s this therapeutic quality to working with him, because we’re reflecting on our own lives.

Is Aksel in The worst person in the world based on someone in particular?

Not really. There was this underground scene in Oslo in the early 90s which was heavily influenced by Robert Crumb. This transgressive talk about, you know, sex and bodily fluids. And when Aksel is on the radio [getting grilled about his transgressive work]it is a moment of profound truth for him.

For Reinate and me, our research was much more centered on relationships, intimacy, the way we spoke to each other in a relationship. We tried to explore every corner possible. Sometimes a scene looks like a big house with lots of doors and potential rooms you can enter. Our job is to get to know this house. We must enter all the doors and see what is there. And we need to know what’s in the attic and in the basement.

What is your next project?

It’s a good question. I have been working as a doctor since we shot this film. In the pandemic, it seemed really meaningful to be able to contribute. I mean, it’s the biggest crisis since World War II!

Comments are closed.